HOUSE PAINT ON MY AIRPLANE?

|

|

By: Charles Threewit

Published: July, 2002 Custom Planes Magazineģ

Todayís modern latex paints are miracles of chemistry.

Someone queried the members of the EAA on their web site about using

latex paint on aircraft, and the responses were interesting. |

|

|

Some people had used it. One gentleman said he was 72

years old and had been in aviation for 55 years. He thought these

facts gave the knowledge to predict dire results from its use.

His attitude, and that of the other nay Sayers, reminds me of when the

Wright brothersí father, a few days before their historic escapade at

Kill Devil Hills, emphatically said to the press that ďIf God had

wanted men to fly, heíd have given them feathers!Ē Or itís similar to

the sagacity of the long-departed IBM CEO, who said, in the late 1970s

that ďAs near as I can calculate, there will be a worldwide market for

a total of about five home computers.Ē

Actually, the following are several good reasons to give serious

consideration to the use of latex paint on fabric-covered aircraft:

*A low cost of about $20 a gallon, compared to several hundred dollars

per gallon for more exotic paints

*Ease of application and total lack of toxicity

*Its tenacious hold on fabric fibers

*Its flexibility

*Its resistance to UV damage

*An infinite variety of colors

*The dealerís ability of computer-match paint samples

Years ago, model aircraft builders who had an aversion to the cost of

automotive-type paints discovered the usefulness of latex paint on

aircraft. And, in many cases, they didnít have the equipment or the

knowledge for proper application of these exotic materials. In

addition, automotive paints require expensive breathing apparatuses;

in curing they give off cyanide and theyíre extremely unfriendly to

the environment. Many award-winning giant-scale model aircraft are

finished with latex paint today, and there are several web sites

devoted to the subject.

Note: To be called ďgiant-scale,Ē a model has to be at least ľ scale

or have a wingspan of al least 80 inches for a single wing or 6o

inches for a biplane.

One excellent article on painting and detailing giant-scale models can

be found at http://www.modelairplanenews.com/how_to/latex.asp. The

author, a nationally known, award-winning modeler, has used latex to

finish his planes since 1983. He had been using expensive epoxy paint,

but he couldnít match the colors on a plane he had repaired after a

crash. He went to the local Benjamin Moore dealer for help and learned

they could match the colors exactly-for about 1/8 the costĖby using a

computerized spectrometer. After refinishing the model with Benjamin

Moore latex applied over conventional automotive primer, he was

surprised to discover that the newly repaired plane was now 4.5 pounds

lighter than the original had been-even with all the extra material

used for the repairs.

Itís interesting that the SR-71 Blackbirds on display at the Blackbird

Airpark in Palmdale, California, were painted with black latex to

protect them from the vicious UV content of the high-desert sun.

During flight, the planeís skin temperature approached 575 degrees F,

so latex obviously wouldnít be suitable for flight. But, it works

great to protect the grounded birds from the ravages of the desert

sun. |

|

|

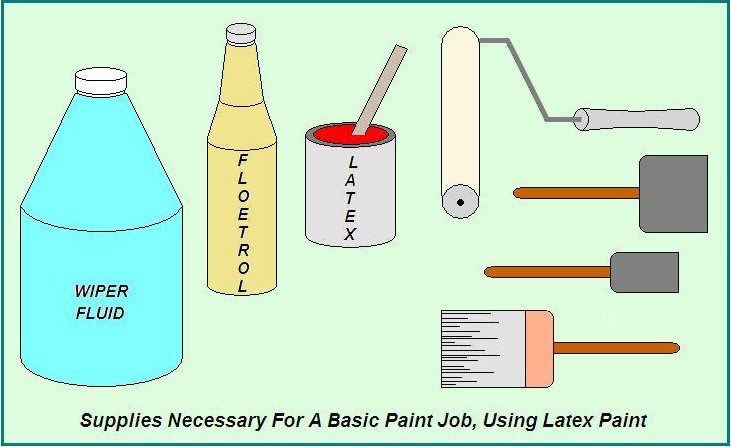

The

picture (above) shows all the equipment required for a basic paint job

using latex paint. In the center is the paint; I used a can of bright

red I had sitting on my shelf. To the right of the paint are a foam

roller, a couple of foam brushes and a good-quality bristle brush. To

the left of the paint is a product called Floetol. It lowers the

viscosity and surface tension of the paint and helps it to spread more

easily, making for thinner coats and easier application.

The jug on the far left contains windshield-washer solvent. Itís an

excellent thinner for latex paint, although the paint folks wonít

recommend it (they recommend no thinning or thinning with water only).

Latex paint contains ammonia and so does windshield-washer solvent.

The solvent also contains small quantities of detergent, which also

contributes to ease of spreading. Small brush marks left in the paint

quickly even out while the paint is still wet and small marks continue

to disappear over the next several days. And cleanup is with water, as

long as the paint is still damp. Like any other paint, it resists

solvents after it dries. After all, thatís what itís for, isnít it? By

the way, latex is impervious to gasoline after it sets.

Latex is also easy to spray, although most folks recommend brushing on

the first coat to control the application of the paint to the raw

covering material, which should be cleaned with MEK to remove any

grease, oil or residue from adhesives. Care must be taken in this

step; obviously, because MEK is the solvent used in the adhesives, and

we certainly donít want to loosen the covering after itís applied and

stretched.

Just as in the application of sealers and primers, care must be taken

not to apply such a heavy layer of paint that puddles begin to form on

the backside of the cloth. Thatís the reason for the recommendation to

brush the first coat, which allows much better control for those of us

who arenít expert spray painters.

Latex doesnít form a chemical bond with the fibers of the covering,

but it forms a tenacious mechanical bond as it wraps around them.

Succeeding coats then form an excellent bond to the preceding coats,

especially if the last coat has been scuff-sanded. Note that latex

paint doesnít like being wet-sanded. Even when itís well cured if itís

kept wet for any length of time, itíll begin to roll up under the

sandpaper. When it must be feathered it must be done with care,

patience and practice.

When spraying my models, I use either an automotive-type touch-up

spray gun or an airbrush. Iíve used my quart-size gun to spray my

house with latex, and it works just as well with latex as the others.

I have a 2-hp compressor I use with the larger guns, and Iíve always

used my small diaphragm-type compressor with the airbrush, although

thereís no reason not to use the larger compressor with it. Itís

essential that the compressor is equipped with water and oil trap, any

minute quantity of oil in the paint will cause it to fisheye. This

will necessitate removing the paint. Fortunately, any goofs we make

can be immediately corrected while the paint is still wet. Just use a

wet rag to wipe it off.

Roy Vaillancourtís Web site has an excellent discussion about the way

he prepares his paint for spraying. He also writes about the

application of the paint. For him, itís usually on fiber glassed and

primed surfaces, but the principle is the same. Start with a very

light coat, and after drying; add two more coats, with the second

being allowed to dry before adding the third. Because the solvent in

latex is water, the paint dries rapidly, depending on the temperature

and humidity. Vaillancourt uses a heat gun to dry the paint on his

models.

One of the neat things about latex paint is its opacity. The old rule

about never putting light colors on top of dark doesnít apply with

latex. Although itís still a good idea to use dark over light, it

isnít a necessity with latex. One manufacturer advertised that its

paint contains 48% solids, by weight, far higher than anything else

Iíve seen, other than polyurethane, perhaps. This certainly accounts

for the high opacity of the paint. |

|

Some

folks who use latex on full-scale planes use a base coat of black

paint for ultraviolet protection. However, if the bare fabric is going

to be visible in the finished plane, the black color isnít too

desirable. An interesting Web site (http://www.larryvile.com/dcd/tandem/latex1.htm)

describes the painting of a Ragwing Ultra-Piet (a ĺ-scale Pietenpol

Aircamper).

The author didnít use an undercoat of black on his Ragwing

because he didnít want the black to show in the cockpit. Also, he says

he was concerned about the weight-saving possibilities. He said, ďIf I

was still flying the airplane in 10 years, it would probably be ready

for new fabric anyway, I figured, UV degradation or no.Ē

Then he describes how he devised what he calls ďan accelerated aging

test, something much harsher than it would see on a hangared

airplane.Ē He prepared a sample of fabric, stretched on a wood frame,

and applied single coats of red and white latex to various parts of

it. Then he placed the sample outside, learning against the south wall

of his shop. He left it there for the next 6-1/2 years. Believe me the

south wall, in Lawrence, Kansas, does get a lot of sunshine!

He tested the sample periodically for deterioration of the fabric, and

only at the end of the 61/2 years was he able to detect any UV

deterioration. He makes no claim for the scientific accuracy of his

field test, but he says it satisfied him to know that his plane could

be safely flown without a black base coat. More than one coat of paint

would greatly increase the opacity of the paint and serve even further

to prevent UV damage.

Thereís some humor included in the description of the test. One of the

lower corners of the test sample, painted white, is severely

discolored. Aha! Have we finally found a weakness in latex paint? Does

it turn yellow when exposed to sunlight? Not necessarily. The author

said the yellowing is the effect of canine urine on latex paint!

Hopefully, that wonít be a problem for paint used on airplanes.

Regarding flexibility, the Web site said the author has taken a

painted piece of fabric, wadded it up tightly in his hand, rolled it

about and opened it back up with no cracking or other damage to the

paint. I visited our local paint store and was shown some test samples

that showed the same result. One was a strip of painted plastic that

had been bent doubles, and then a larger weight was applied to fix the

crease. This didnít damage the paint. This flexibility makes the paint

suitable for use on unsupported fabric surfaces that will be subjected

to flexure during normal flight service.

Latex manufacturers all recommend their paint for use on metals and

fiberglass that have been prepared by scuff sanding or the use of

etching solutions and then carefully cleaned. The EAA site has a query

from an aircraft owner seeking information abut how to get latex off

an aluminum-skinned plane. If latex has a fault, itís that itís

impervious to most, if not all, of the normally used paint solvents.

There are solvents available that will remove it, however. Check with

any well-stocked paint store with knowledgeable salespeople.

Most of the large paint stores now have computerized spectrometers

they can use to match any paint sample. The sample is placed in the

spectrometerís viewing window, the computer takes a few minutes to

analyze the color components of the sample and then it prints out a

formula for mixing the paint. Lighting and eyeballs are removed from

the equation. The color chips, that are available at most stores, show

the complete spectrum form which colors can be chosen, and the

computer can match anything in between the chips. This is particularly

useful when trying to repaint repaired surfaces after the surrounding

paint has been weathered enough to begin fading. The computer sees the

sample, as it is, not what it used to be. The formula it gives matches

what it looked at. There may be a difference in the gloss of the

weathered paint and the new paint, but that can usually be taken care

of with a good wax job.

It seems that homebuilders are really missing something if we donít at

least look at the possibilities for using latex paint on our projects,

the nay Sayers not with standing. Where would we be if the Wright boys

had listened to their nay saying father without at least testing their

ideas?

The above courtesy of

http://www.lightminiatureaircraft.com/generic31.html

|

|

|

RagWing bi plane painted with house paint. |

|

|

|

1 2

3 4

5 6

7 8

9 10

11

12 13

14 15

16 17

18

19

20 21

22

23 24

25 26

27 28

29

30

31

32 Index for this section. |

|